The multiple-choice question has been a staple of educational assessment for generations and that makes sense. They are easy to create (unless of course we design good ones) and they are easy to administer and to grade.

Educators also find they are very comforting. We can have confidence that students who give the correct answer to a question know the answer, have understood the material, and by extension that we have done our job well. What more could the “data-driven” educator want?

If one truly is data-driven, they will understand our confidence is not justified.

Let’s consider a single question on a test (a multiple choice with hour options) and every student provided the correct answer. The first assumption we are making is that the question is unambiguous and there is a single correct answer that the teacher has accurately written and there were no mistakes in grading. This may or may not be true, but let’s assume that (perhaps through review by others) the question and answer are accurately paired and that (perhaps through using computer-based testing) the question is accurately graded.

In my hypothetical question, the answer is “A.” Consider the explanations for “correct” answers that actually tell us little about what our students know:

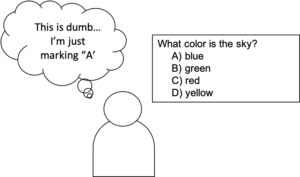

1) Students may have marked a random answer. With four options, 25% of the students who answer at random will get the correct answer.

2) The student may have meant to mark “B,” but marked “A.”

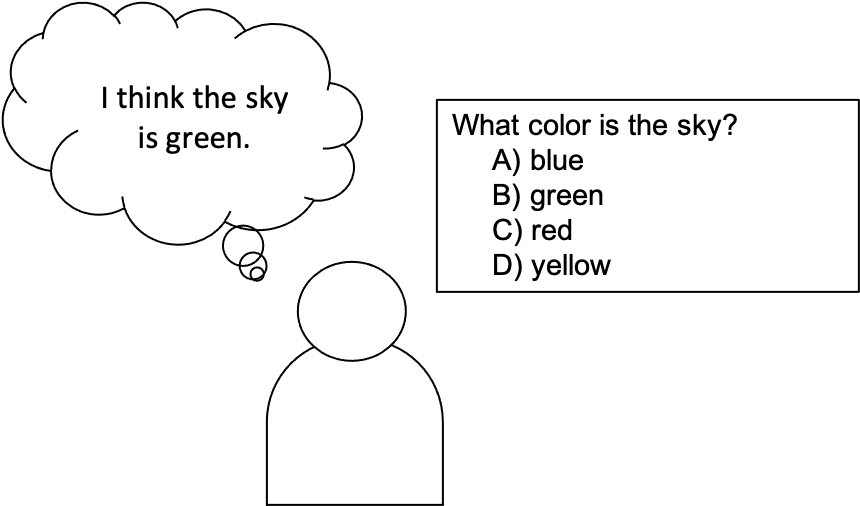

3) The student may have misinterpreted the question and that question may have also had the answer “A.”

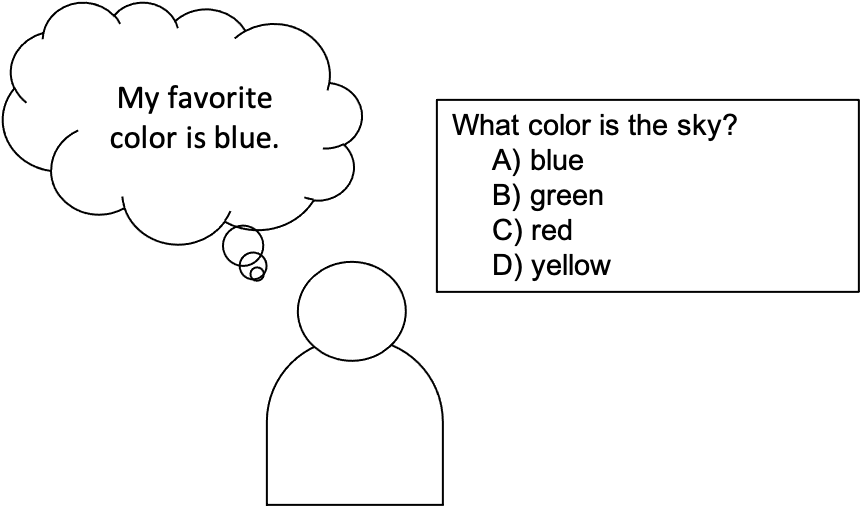

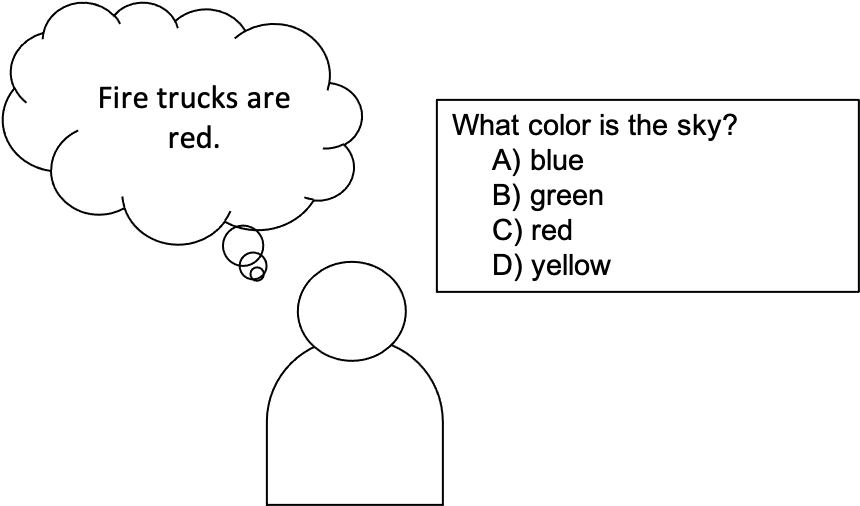

4) The students may have misinterpreted the question and provided the wrong answer to that question.

The opposite situations should be recognized as well. Students who provide the incorrect answers can be explained with the same situations. All of these situation and others are sources of error in our measurements. No matter how careful we are in the design of our tests, these errors will affect our measurements.

My point in writing this blog is not to rant against testing. My point is to suggest educators should be much more realistic about their instruments and their data than they usually are. If you are going to rely on tests as your assessment of your students at any level then you have the duty to accurately understand what is being measured (or not measured) and to avoid self-delusion about their data.