Here is my second post on the theme “epistemology is not a four-lettered word.” In this series, I am considering the philosophy of knowledge and the assumptions about the nature of what is known. My rationale is grounded in my belief that educators should recognize the role of epistemology in the design of their classrooms and their lessons.

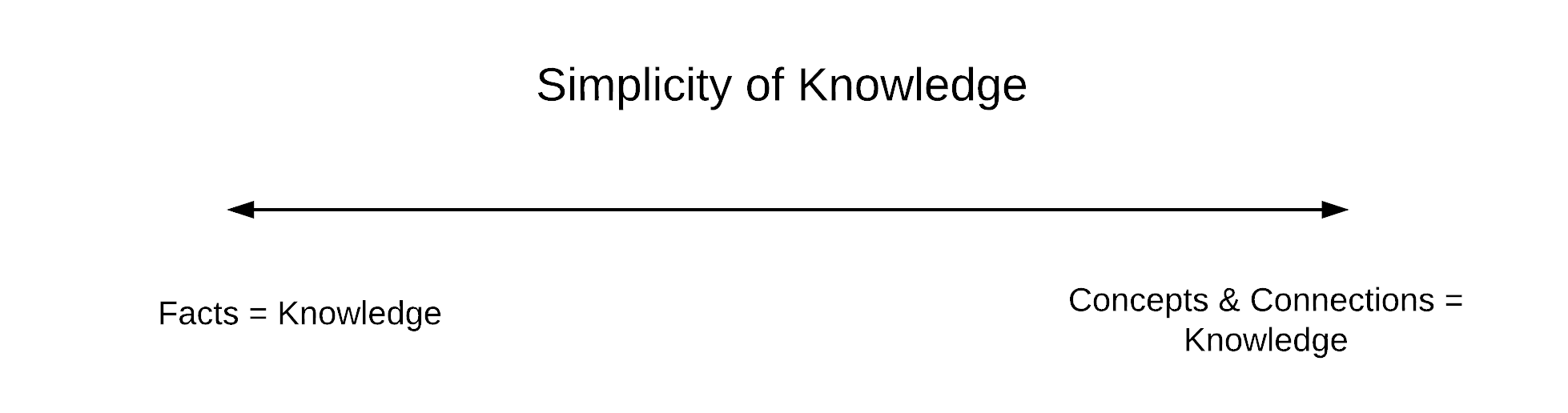

The second characteristic of one’s epistemology focuses on the simplicity of knowledge. For some knowledge exists as “facts.” Facts, of course, can be a surprisingly difficult and contentious concept. Epistemologists who believe knowledge exists as facts post facts are objective (everyone agrees) and discreet (clearly bounded). For one to demonstrate knowledge, it is sufficient to identify facts about the subject.

When we give students the assignment to “find five facts about an animal,” we are approaching knowledge as a simple phenomenon. We assume that “carnivore,” “lives in Africa,” “can run fast,” weighs 200-400 pounds,” “mainly nocturnal” are examples of knowledge about lions.

This assumption is opposed by epistemologists who hold knowledge exists in the generalizations, interpretations, and connections that exist between “facts.” This is a more complex and sophisticated understanding of knowledge as we often frame knowledge with “it depends.” For example, these epistemologists recognize lions are held in captivity in places far beyond their original range. They will suggest the sexual dimorphism that characterizes the weights of lions is meaningful knowledge whereas the range of the smallest females to the largest males is not.